“Claybodies”

Reinterpreting the Figure

Hunterdon Art Museum, Clinton, New Jersey. February 27 - June 12, 2011

Two works by Paola Borgatta

This excellent show, co-curated by Ingrid Renard and Hildreth York, is presented with a statement by the curators which I found somewhat provocative, if not altogether accurate. They said, in part:

“Clay…demands a direct involvement of the shaper’s hands, unlike other modes of sculpture where tools, whether simple or complex, must mediate between the artist and the work. Perhaps in an era defined by technology it is deeply satisfying to be so connected to a material which is so essentially earth.”

While it is certainly possible to work with clay and use a minimum of tooling, I don’t know of anything about clay that makes it immune to technology, any more than other materials. One can cast or press clay into molds just like metal, and these molds, or the masters for them, can be made by computerized carving or additive techniques. It’s even possible to build 3D prints in ceramic by consolidating clay powder with a binder applied via ink-jet technology—untouched by human hands (video). In fact, the Shapeways, site which makes these technologies available for the general public, recently added a ceramic material to the options it offers. When one invests a work of art with romantic expectations about the primitiveness of the process involved in making it, does the satisfaction disappear when one finds out that it was actually produced using highly technological means?

Leaving that question aside, this show presents a range of approaches to figurative sculpture, and clay is utilized in various ways from the most basic—modeling it directly with the fingers—to the relatively remote process of making a highly-detailed clay model, taking a synthetic rubber mold from that, and casting an edition of sculpture in high-strength gypsum cement. The work of Paola Borgatta is an example of this first method; her deceptively simple arrangements of female figures engaged in domestic tasks or arranged in tableaux were achieved with a minimum of technical contrivance but a high level of skill. Deliberately eschewing the seductions of color and shine, these small-scale works in brown stoneware have a quiet timeless air about them that validates the curator’s intention to seek out the primary products of hands and clay. But most of the rest of the artists in this show deviate from this ideal to some extent. Personally, I don’t have a problem with that—any technical means artists choose to utilize which helps them achieve their vision is fine with me. Of course, if one avails oneself of the benefits of high technology, then higher expectations are aroused, just as one expects more speed from a Nascar event than from a footrace. In this show, however, none of the artists seem to be engaged with any technology that’s particularly advanced, and most could comfortably have done their work with the methods available a century ago—but that’s not to say that their aesthetic sensibilities would have aligned with those of that period.

If any theme characterizes the wide variety of work on display here, it is metamorphosis—the classical ideal of the human body has generally been discarded in favor of heterodox fantasies—or nightmares—that the very different imaginations of this collection of artists have brought forth into tangible reality. Disembodied heads on pikes by Judy Moonelis, adorned with lacy jewelry, glance down on an empty set of feet surrounded by broken glass. Tom Bartel’s armless mutant children assume shamanic roles in worlds a bit different from our own. Some of these artists have ransacked the closets of art history to come up with pieces that straddle the divide between present and past, like Kukuli Velarde’s “Indianus Zopilotense” and “Pacharatense Indianus,” or Akio Takimori’s “Venus and Island 4” which refer to ancient tomb sculptures of the Western and Eastern Hemispheres while keeping one foot in our own time. Others seem to hark back to the punishments predicted for sinners in the afterlife: Adrian Aeleo’s “Gathering” shows a person in a repentent posture, being colonized by birds in her back, while Bruce Dehnert refers specifically to eternal damnation in his “Hades Revisited.” Mike Prather portrays the victims—or tortured perpetrators—of these otherworldly castigations with his dunce-capped—or inquisitorially-garbed—busts that plead with us to “Kiss me Baby.” Mark Frank’s “Split Head” is just that—perhaps a graphic portrayal of the right-brain/left-brain divide, or the dilemma that faces those who want to live in the real world as well as inhabit the world of art.

Splitting and hollowing out seem to be popular metaphors among the artists in this show; I’m not sure if they are employed as political or psychological commentary, or just an extension of the normal processes of ceramic practice, but Etta Winograd also employs it explicitly, in her smoked-clay piece called “Split,” in which an impassive iconic figure (Mother Earth?) averts her gaze from the small people restlessly climbing and delving in her body. Rob Kirsh takes a more cerebral approach, removing pieces from a hollow fetally-crouching figure and the hand that shelters it in “Nursery” until just a framework is left to reference the body. Sergei Isupov’s approach was different from most of the other artists represented here, in that he uses sculpted human and animal figures as a canvas for illusionistic painting, which works against the recognizability of the base sculptures in much the same way that all-over tattoos alter our perception of people’s bodies, when their skins function visually as the background for graphic art.

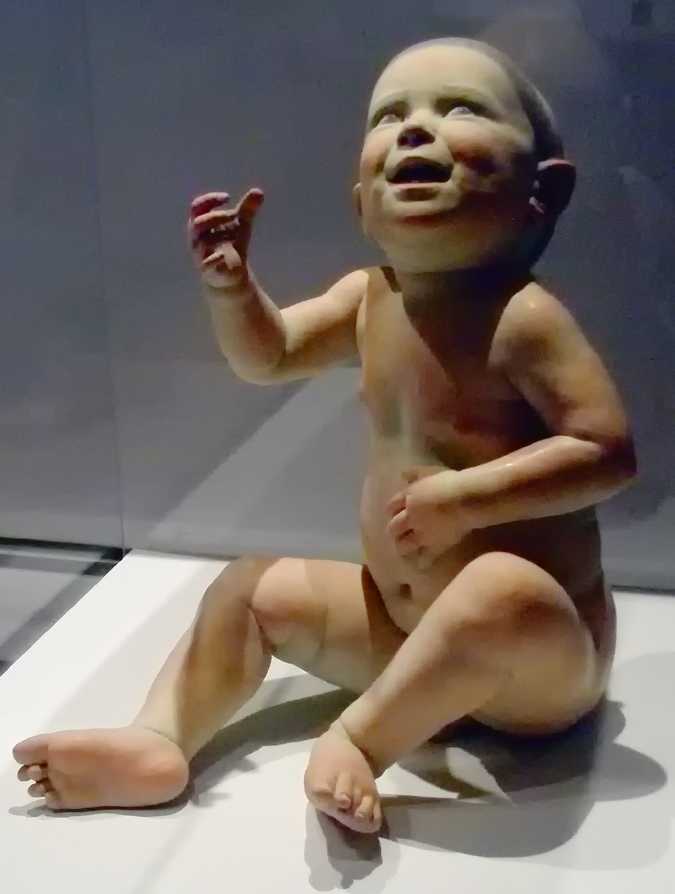

A few works were anomalous in the context of this show, and made me wonder why they were included. Judy Fox’s hyper-realistic portrayals of over-sized infants, unlike the rest of the pieces there, were not composed of ceramic at all, but were cast in Hydrostone, a type of gypsum plaster, or in “bonded marble” which is basically a plastic resin, using rubber molds. It’s hard to reconcile the curators’ rhetoric about the direct involvement of hands in clay with pieces like this in which the shaping is done early in the process and what we see is the result of a technical process at some remove from the act of fashioning. Certainly it can be argued that this is the most appropriate means for this artist to achieve her particular vision, and I have no problem with that, but it seems somewhat at odds with the stated themes that were supposed to underlie this exhibition. The other piece that didn’t quite fit was a plate by Viola Frey, which is basically flat where every other piece is in the round, and doesn’t really present a body of any sort but rather features a disembodied face and hands. Perhaps it was meant as an homage to the late sculptor, who stood her ground as a champion of figurative art and craft techniques in an era in which these things were anathema to the critics who ruled the art establishment, and a way for her to be present in spirit, if not to actually participate. In any case, I think she’d be glad to see the resurgence of the things she stood up for, as exemplified in this strong and diverse exhibition.

Andrew Werby