Siggraph 2008

Scary Female Robot

I hadn’t attended Siggraph, the big summer computer-graphics conference and exposition, in a while so I made time for its 2008 incarnation in L.A. I’ve been to Siggraph a couple of times before, and always found interesting things to feed my thoughts during the rest of the year—happily, this year’s show was no exception. If you’ve never been, it’s part trade show, part art exhibition, science fair, jobs fair, academic symposium, and general geek-fest.

The world of computer graphics, widely defined, has grown so huge and diverse that what started out as a small gathering of enthusiasts for an obscure artistic/scientific pursuit has grown into a huge venue embracing worlds as diverse as Hollywood film-making, game development, print advertising, video animation, product prototyping, 3D visualization, computer programming, and website construction. Somehow, Siggraph manages to straddle them all, and provide something for everyone.

The show seemed more compact than in the past, either because of America’s current economic woes, or consolidation in the industry necessitating fewer booths. The “Guerilla Studio,” where one is able to participate in activities like scanning a part, designing a lenticular placard, or seeing ones 3D models built with a 3D printer shared the main exhibition space with the art show and the vendors, instead of being tucked away in separate rooms of their own, as had been the case in previous shows. Some of the people demonstrating odd projects (a favorite part of the show for me) were also there, although some were placed outside in an annex. In the Studio, I was fortunate enough to meet Dennis Dollens, who embodies the original techno-artistic spirit of this event. From his deep analysis of biological form, he has extracted algorithms that create spookily natural-looking “biomimetic” trees (which he sells to people making games and movies) as well as twisted “digital-botanic” structures that appear to have evolved under the influence of powerful mutagens. There was also someone there demonstrating the Gigapan system for creating panoramic photos that were huge and seamless. It involves a special camera mount and some software, but not a lot of expense, and includes membership in a site that allows participants to share, exchange and even sell their panoramas.

Taisuck Kwon’s “Robotic Emotions”

Erik Dyer’s “3D Zoetrope”

Projects in the Tech Demos area included a landscape generator set up like a bar, where one could order a mixture of plants, earth, sun, moon, sky, and water, each quantified by bottles of liquid set in a weighing station. When these ingredients were agitated in a cocktail shaker, a unique landscape would appear on the monitor, with all elements in the desired proportions. Michela Magab was demonstrating a music-sorting system, which could instantly match an excerpt with a vast collection of audio stored in a database, to identify copyright violations, plagiarism, or simply to find pieces similar to those one enjoyed previously.

Ph.D. student Taisuck Kwon brought a flayed robotic face capable of showing various emotions with programmed activation of artificial musculature while Jonathan Chertok was displaying a set of rapidly-prototyped versions of classical mathematical models.

Another Japanese group had made a “friendly” robot with doll-like features and a soft feminine voice that I found scarier than most movie monsters but maybe that’s just me…

Some projects were educational in intent, like the Calakmul simulation game by ArcVertuel featuring the ancient Mayan site as the background for a videogame-style quest intended for a kiosk in a children’s museum, or the more ambitious “Rome Reborn” which allows one to “walk through” seven thousand digitally-reconstructed buildings of the ancient city, as it appeared in AD 320. Others, like Erik Dyer’s modern 3D zoetrope in which solid objects produced via Rapid Prototyping come to life on turntables seemed basically artistic, although they may point the way towards new techniques in film-making. Interactivity and haptics (tactile feedback) were also a major focus in the tech demonstrations, with some devices, like the “Butterfly Haptic” trying for a new way to relate to objects previously only seen on a monitor, or pointing the way towards remote-controlled sex (Emotional Touch) and using touch-feedback to add a novel, if not altogether comfortable, dimension to users’ interactions (“Ants in the Pants”).

I especially liked the exuberant sculpting of the “Infinite 4-D fish” by Yoichiro Kawaguchi of the University of Tokyo which while reminiscent of Takashi Murakami’s work in its bright colors and slick surfaces, managed to restrain the “super-cute” content elements that some seem to like but tend to make me gag.

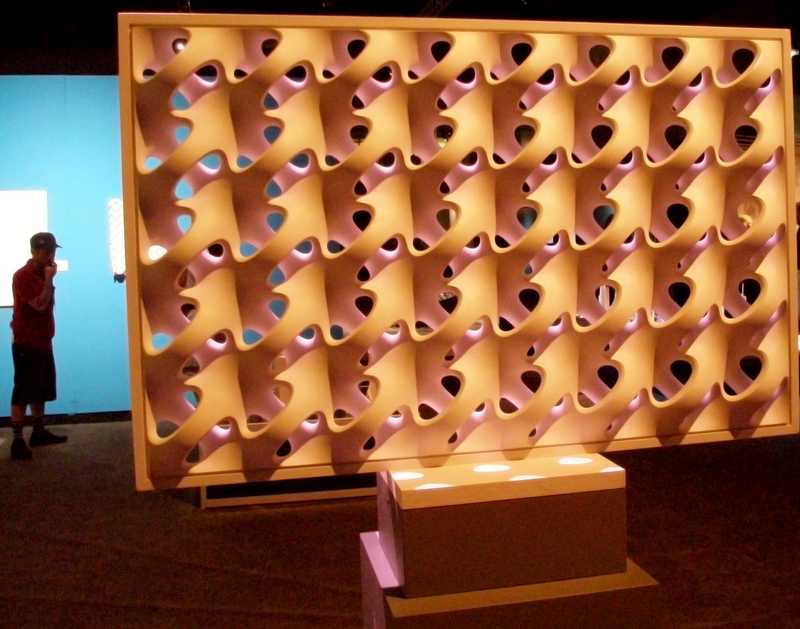

The art show, which had been inspirational in the past, was a bit flat this year, with few examples of sculpture shown despite the spread of 3D printing and affordable CNC equipment. Perhaps it was the choice of theme: the idea of Slow Art doesn’t exactly set pulses racing. Bathsheba Grossman’s new work in direct-metal RP was an exception—her topographically complex yet pleasing forms had a solidity and timelessness rare in a realm dominated by ephemeral materials and artistic fads. Much of the space was taken up with a display of skyscraper models, which, while they demonstrate how RP techniques have taken hold in the architectural modeling field, didn’t exactly break new ground in art. I liked the large pierced panels created by Erwin Hauer and Enrique Rosado using CNC milling, which, though reminiscent of other work in the math-art field, did show how this sort of thing might be integrated into an architectural setting.

Mo-cap Demo

Out on the expo floor, a wide range of vendors competed for the attention of the passing throngs. Motion capture was a big deal here, since by tracking targets placed on a live actor, a lot of tedious animation can be bypassed, and the motions directly mapped to a digitally-created image in real time. There’s also facial mo-cap (as it’s familiarly called) exemplified by the “alter ego” system which can quickly and automatically keep track of the shape changes in an actor’s face and apply them to any sort of animated character. The latest systems dispense with the targets, and manage to follow the motions of a digital image. I was impressed by the work of some Japanese investigators from the University of Tsukuba in the tech demo area, who had figured out how to analyze the motions of a hand captured on video, which they used to control a “copycat” robotic hand in near real time.

Much of the expo space was taken up by major software producers demonstrating their newest products on big screens to scores of seated viewers happy to get off their feet for a while. AutoDesSys, makers of FormZ, was premiering BonZai 3D, trying for a product that is simpler and easier to use while perhaps more “geometrically robust” than the flagship product. Other software developers are thinking along the same lines. At a much smaller booth, I was able to get a personal demo of MOI, short for “Moment of Inspiration” from Michael Gibson, who wrote the program himself, and could explain everything about it. Having been largely responsible for creating Rhino3d for Robert McNeel, he struck out on his own to make a simpler, faster, more affordable 3D modeling program for designers and artists, using Rhino’s model of an extended free beta period and active user forum to refine the interface and root out bugs. After years of this, MOI is finally being sold instead of given away, although you can still download a 30-day demo and tell everybody what you think of it.

I was interested to see a demo of T-splines for Rhino which helps Rhino deal with organic geometries by allowing T-joints instead of the rigid grid topography that characterizes Rhino’s NURBS, where every spline must cross every other to create a valid surface. They were also talking about using the program to create NURBS surfaces from polygon meshes, which would be worth the price of admission right there if it worked smoothly.

A 2D program called Toonboom, used for producing several of the animated sit-coms popular on TV, was showing off a reasonably-priced “Studio” version aimed at the masses huddled around YouTube, yearning to produce their own cartoons. The demo made it look reasonably easy to use, but they always do that…I was also intrigued by Mathematica, a multi-faceted set of applications, widgets, and libraries which has survived for 20 years by taking a different approach than most companies—assuming that their users are smart and willing to learn new tricks. Since the academic pricing is good, it would make sense for bright students, teachers, or researchers in a number of technical fields, like Mensa in a jewelbox.

Several companies were showing off 3D scanners of various sorts. Immersion had their latest Microscribe, and the RSI laser that mounts on it, enabling a user to capture various angles of their models intuitively, positioning the laser by hand. It’s a proven solution (and one I already sell), but it was nice to see how easy it is to use. I was able to see the NextEngine scanner digitize a small part, and was impressed that it worked as well as it did. But the most exciting development was Creaform’s new VIU hand-held color scanner, which does a super job of capturing geometry as well as the photo-textures it automatically maps to the surfaces. It requires “targets”—small reflective dots applied to a large or complex model—to register a series of different scanning passes, but this allows objects of considerable size to be captured, as well as multisided objects requiring multiple points of view for a complete scan. They were able to show digitizations they had done of very complicated parts, like a tree with all its leaves, and a huge multi-level fountain, with multiple sculptural figures in place. Of all the things I saw at Siggraph, this is the one I most wanted to take home with me.

While nobody was trying to sell CNC machines to this crowd, there were several vendors of additive RP machines at the show, including Z-corp and Objet. Z-corp machines work by ink-jet printing a binder solution into a bed of powder, which slowly sinks on its piston as successive layers of powder are applied and consolidated by the binder. Since the part being built is always supported by the powder that surrounds it, it’s not necessary to provide the extra supports required by most other systems, which saves time and effort. And since one is ink-jet printing anyway, it’s possible to add color at the same time in a controllable way, even to the extent of printing color photos on the sides of the part. But the part as printed lacks strength, and must be impregnated with some kind of resin or wax before it’s good for much, while the surface is always a bit grainy. Objet was showing their Polyjet system, which gives much smoother and more durable results, but not in full color. They have, however, the ability to print in more than one material at a time, so bicolored parts are possible. While the process requires supports, it can build them in a material which can be dissolved without harming the material you wish to keep. It also allows you to use rubbery materials with varying durometers (degrees of softness) so that humanoid parts could be made with hard bones, for example, in soft flesh, all at the same time.

As well as companies trying to sell RP equipment, there were others trying to sell it as a service. Shapeways had an interesting concept, providing a wizard on their site which lets users construct objects from lines of text, that (for a price) they could then have built with a 3D printer, and have shipped to them. While not many options were available yet, this is a compelling business model, allowing people to produce personalized gifts without the requirement of craft skills.

Not only were companies there trying to sell things, quite a few organizations viewed this event as an opportunity for recruitment. Numerous schools were there pitching their audio-visual, computer-animation, and game development curricula, such as Cogswell College, Collins College, UArts in Pennsylvania, Florida Interactive Entertainment Academy, and the oddly-named DigiPen Institute of Technology in Washington. Turbosquid and Renderosity were promote their online “communities,” where people can sell digital models to one another, and of course Siggraph itself was soliciting members for its own Digital Arts Community site. Several big software and animation houses were looking for employees (mostly software engineers) and even the U.S. Mint was there with some Phantom haptic arms from Sensable Technologies looking for a few good traditional medallic artists willing to use digital tools to create coin sculptures.

If there was any noticeable trend to spot here, it’s the new prominence of stereoscopic display systems, mostly based on polarized stereoscopic images and shutter-glasses. Of the two, the shutter-glasses work best, although they cost more and are more difficult to implement. The old style red-blue anaglyphic system seems to be on its way out, which I don’t mind much, since it never really worked very well. It has been replaced by polarized stereoscopy, familiar to those who have visited Disneyland in the last decade or so, which works by projecting two rolls of film (or video streams) that were shot from 2 viewpoints that differ by the interocular distance. The images taken by each camera are filtered through a polarizing lens on the projector, so each is only visible to one eye, when you’re wearing the special glasses that block out the left image for the right eye and vice-versa, while letting in the image corresponding to the viewpoint it was shot from. The shutter glasses accomplish basically the same thing but more positively, by winking each eye alternately on and off very quickly, while images intended for one eye only alternate on the screen. Persistence of vision makes the 3D illusion work, since the eye holds onto the image it’s given without realizing that it has been turned off for a tiny moment. The brain takes in the different input from each eye and creates a 3D image, as it does for normal vision.

One company, Digital Ordnance, had stereo cameras aimed at the crowd, and were projecting our large-scale 3D images right back at us on the walls of their booth. It was a pretty convincing illusion, once I put on the glasses. They say they can provide a complete capture, storage, and projection system for $60k. Since movie theater owners are desperately looking for something that will get people off their couches and back into the theaters, more and more of them are equipping their venues for 3D polarized display, shutterglasses being impractical for a large audience. The success or failure of the current crop of 3D movies will probably determine if this trend will continue or be abandoned like the anaglyphic 3D system of the 1950s. The price of 3D digital projectors for individual users is also dropping, with one company, Lightspeed Design, introducing the DepthQ system designed to work with shutter glasses and able to project a high-definition 12-foot (diagonal) stereo image, for less than $6k.

Eon Reality’s “Porsche”

Of all the companies vying to be at the forefront of 3D digital content creation, Eon Reality seems to have the most going for it. They have made it their mission to conquer the world of immersive 3D, using it for marketing, education, training, and entertainment. At the Siggraph show, they were showing a full-sized Porsche automobile projected on a semitransparent semicircular screen, a 3D image that worked without glasses. The restrictions of their booth didn’t allow them to present the full range of what they have developed, so the day after Siggraph closed, I went down to their Irvine headquarters to attend their World IDC Symposium, in order to check out some of the other technology they’ve come up with.

I was not disappointed. These people have been working at this for a while, have written software and assembled hardware that allows them to create immersive 3D content in a variety of forms. The meeting was addressed at times by a convincing 3D projection of a speaker, who was able to sense and react to the audience without actually being present. They had 3D TV working, with wireless shutter glasses that felt light and comfortable. They had a system for projecting movies into a heads-up display that fit in a pair of eyeglasses. They’ve developed web-based software, Eon Human, to generate multiple views of a user’s own face from a single 2D image, useful for creating quick avatars in an online multiplayer game. They had software that let them make changes to a virtual 3D environment and render them instantaneously, without the lag time typical of 3D rendering programs.

Most impressive of all, they had constructed a space (the “cave” aka ICUBE™) where multiple projectors created an almost palpable 3D image for a shutter-glasses and headset-equipped viewer. The headset oriented the view to the viewer by tracking the direction of view, while the shutter glasses created a very convincing 3D effect—an exploded view of a jet engine with all the parts floating in space right in front of me. (The main problem they had with it was preventing disoriented users from crashing through a wall). For companies needing to train their employees in the use or repair of complicated equipment, where the equipment itself would be too complex or expensive to work with, for schools needing a way to break through the ennui of the traditional lecture format and engage their students more directly, for marketeers wanting to break through the clutter of competing trade-show exhibits, for applications of the future like virtual tourism and 3D telepresence, these would be the folks to contact first.

Siggraph’s 36th annual event will be in New Orleans next summer, making it more accessible to people in other parts of the country. To join, exhibit your work, or otherwise get involved, you can contact Siggraph ’09.

Andrew Werby