Jewelry Masterpieces

French Jewelry from American Collections

San Francisco’s Palace of the Legion of Honor Museum

René Lalique’s Winter Landscape

This show, at San Francisco’s Palace of the Legion of Honor Museum, traces the trajectory of jewelry-making in France from the Art Nouveau era to present times. Perhaps it’s unfair to try to analyze a country’s production from what a disparate bunch of foreigners happen to bring home with them, but either American taste went into eclipse during that period, or the exhibit charts the decline and fall of a great art tradition.

The show is arranged chronologically, and starts out well with some outstanding examples of René Lalique’s work in enameled gold, with other materials such as horn, ivory, opal and pearls tastefully integrated. Some large bronze sculptures, in the shape of insectile women, originally used as case decorations for his breakthrough 1900 exhibit in Paris’ Exposition Universelle, show his versatility. (Although he became famous as a jeweler, he eventually gave it up and went on to even greater success in glass, although these works, in my opinion anyway, never rose to the artistic heights achieved in his jewelry.) His genius was recognized early, with a first prize given to his multi-part Iris Bracelet in enameled gold with opal background in 1897; and the piece, included at this exhibit, still seems fresh and novel today. Among Lalique’s other works shown, a figurative umbrella handle in horn and gold and a purse featuring mirrored vipers in silver and embroidered leather stand out for their strength and adventurous spirit.

Other jewelry houses of the Art Nouveau period are represented as well, notably Georges Fouquet and Frederic Boucheron. Working with similar techniques, materials and subject matter, they never rise to the same heights as Lalique, but nevertheless manage some fine pieces, like Fouquet’s Winged Chimera brooch, notable for its flowerlike settings of what appear to be American natural pearls (subject of a “pearl rush” at the turn of the century) and Boucheron’s Acacia brooch, with its finely-rendered blossoms in plique-a-jour enamel, or a Butterfly brooch, where the wings of the insect are fashioned from tabular plaques of engraved diamond. Perhaps to remind us that no movement, of itself, can be guaranteed to produce nothing but masterpieces, the show includes some undistinguished works in the Art Nouveau style, mostly “maker unknown,” generally featuring the images of young women, juxtaposed with stylistically rendered verdure, that have come to exemplify the movement in the minds of many.

Moving on to the Edwardian era, the exhibit shows how quickly the world of fashion takes up and then discards an artistic style. While enameling is still practiced, it mostly is used to cover guilloche work (also called engine turning, used to engrave gold with mechanically accurate repetitive cuts). The nicest example shown is a tiny pencil-holder by the Husson workshop. Diamonds are a lot more prominent than before, largely due to the exploitation of the vast South African deposits found early in the century, which fueled the ultimate development of the “Garland” style, based on stylized ribbons, bows, and floral wreaths. Platinum was also introduced to the jewelry industry at about this time, and this seems to have contributed to the development of ornaments that used a minimum of metal (platinum, while it doesn’t tarnish, is quite a bit heavier than gold, let alone silver) while maximizing the use of stones, principally diamonds. The best example of the style shown here is Cartier’s Bow brooch, which relieves the monotony with panels of carved quartz crystal; an example unfortunately unheeded by subsequent designers featured here, who seem to have conceived their task principally as providing a vehicle for diamond sales.

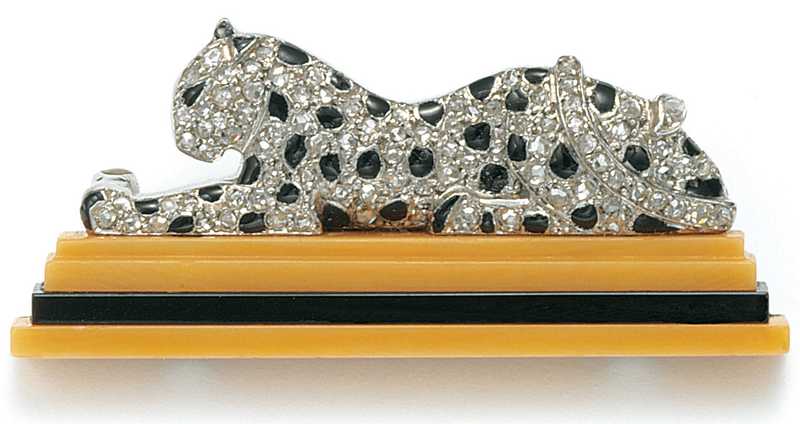

The Art Deco movement brought some fresh air into the world of French jewelry, with its emphasis on bold geometric designs. However, I suspect it was less popular with visiting Americans than at home, since most of the examples on view here are weak and somewhat atypical. A standout piece is a vanity case by LaCloche Freres, with an arrangement of roses in carved red coral, set off by lapis leaves. A jazz band charm bracelet, maker unknown, is a truly charming piece—a row of tiny geometrically simplified musicians and their conductor are composed by arranging odd-shaped stones with a minimum of metalwork, but it has the appearance of a novelty item designed for impulse purchase, not a serious artistic effort. The best example of Deco aesthetics on view is a Panther Brooch in platinum, diamonds, and black onyx (for the spots) created by Cartier for the American boxer Gene Tunney, as a present for his wife. Unfortunately, most of the more serious work has a clunky feel to it, of being constructed to make an aesthetic point rather than to be easily worn, or to complement the wearer. Perhaps this is why many of the examples from this prewar period eschew Art Deco entirely or in part and draw from historical styles, using Chinese, Egyptian, Medieval, Greek, and Mughal forms and motifs. I was struck, however, by the wide range of objects that were considered fair game for a jeweler of this period. Not just rings, brooches, earrings, necklaces and bracelets—they decorated opera glasses, produced dress clips, vanity and cigarette cases, cages for animals, purses, clocks, watches, fans and perfume bottles—it seems that a jeweler’s field of work has narrowed considerably since then.

The Postwar period seems to have marked a low point in French jewelry design, at least from an artistic perspective. Perhaps the atmosphere of scarcity or the recent trauma caused designers and their customers to retrench, but the results as seen here are lamentable. Designs were either derivative of historical patterns or suffused with the blandness that still characterizes the 1950s in our minds. In searching for more inexpensive products, colored stones were used more, but usually in standardized cuts and unimaginative designs. Perhaps copying the taste of the (American) Duchess of Windsor, a vogue was created for cute jewel-encrusted animals, but these did little to alleviate the prevailing artistic emptiness of the period. A new burst of diamonds and advertising from DeBeers, reflecting their monopoly in the world market, revived the Garland style in a simplified form, and jewelers evolved the pave technique to cover everything they made with the small round brilliant-cut diamonds that were becoming ubiquitous at the time.

The main innovation of the current era, according to this show, seems to have been the introduction of the “miracle” or invisible-setting technique. This allows stones, particularly rectangular ones, to be set edge-to-edge, without any metal showing in between. Several examples are on view, but none of them are very interesting from an creative standpoint. Yes, concentrated areas of gem color could now be created, but no—this would not be used to any great advantage, at least not here. Although technical tours de force abound, like the invisible-set ruby. sapphire, and diamond Flower Brooch created for the USA 1976 Bicentennial by Van Cleef and Arpels, no new ground was broken in artistic terms by the mainstream jewelry houses featured in this exhibition. The show does present some self-consciously avant-garde pieces designed by prominent modern artists such as Pablo Picasso, Jean Arp, Man Ray, and Andre Derain, but while striking, ultimately these are unconvincing, consisting mostly of large slabs of high-karat gold in the artist’s trademark shapes. One is left with the impression of artists otherwise committed who are willing to experiment with the jewelry medium, but only on their own terms, unwilling to adapt the mindset of a jeweler along with his materials. French artist Arman is an exception; his bracelet composed from musical instruments in gold successfully translates an essentially sculptural idiom into a workable piece of jewelry.

Striving, evidently, to end this show on a high note, the organizers rely on a single transplanted American: Joel Arthur Rosenthal (known as JAR) to convey the impression that French creativity in jewelry is not altogether dead. And in part, they succeed; his most interesting piece, a jewel-bridled circus zebra carved in variegated agate and surmounted by an elegant diamond-studded plume, recalls the heights of the Art Nouveau period, while his Blue Butterfly brooch refers back to the Deco period. The piece that hints the strongest of the artist’s own proclivities is a Daliesque Sea Urchin Clock, with its granulated gold setting for a sand-backed watch movement placed precisely in a natural urchin shell. But one is left wondering, what is being left out? Surely there are French jewelry makers commanding an original contemporary vision as well as the exacting traditional techniques preserved in Europe that enable them to express it; why aren’t they represented here? Is it that they’ve been unable to reach American customers, or that these collectors are not the high-profile types solicited by the organizers of this exhibition? For the answer, we must wait on some future sequel to this show that is more inclusive in its scope.

The Masterpieces of French Jewelry show is accompanied by a $29.95 catalog/book of the same name by Judith Price, published by Running Press of Philadelphia and London. While the pictures are nice, some are of pieces I saw in San Francisco, others are not. While many of the pieces I saw are in it, many are left out, their places filled with photos of related objects that may have been featured in a different incarnation of the show, or just shuffled in to fill things out. The rather sparse text doesn’t add much to the captions that accompanied the show, but it is annoyingly filled out as well, with fawning interviews of various peripherally-related celebrity figures like Christopher Forbes and Dina Merrill Hartley (heirs of collectors) novelist Barbara Taylor Bradford, and designer Juan Pablo Molyneux randomly interspersed.

The show runs through the 10th of June 2007 at San Francisco’s Palace of the Legion of Honor Museum. The $10 admission fee lets you into the permanent collection, featuring choice works by various European artists and a small collection of antiquities, as well as this special exhibit. While I can’t be equally positive about all the items in this show, it’s well worth the price of admission for the rare chance to see the infrequently-displayed works in the Art Nouveau section. If you can’t make it to San Francisco in time, wait until the Lalique pieces are back home at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore Maryland to see them there—this is the world’s best Lalique collection outside the Gulbenkian museum in Lisbon.

Andrew Werby